WORDS Katie Vega PHOTOS Jon Kohn

Cloverdale Playhouse director Randy Foster puts it perfectly—theatre happens in the space between the audience and the actors.

There is something about theatre. Maybe it’s the fact that you are watching a story happen right before your eyes, acted out by real, live people. Or it may be the fact that you know you are experiencing something beautiful that you will never see again, except in your memories. Whatever the reason, the art of theatre is something to be experienced and our city has many opportunities to live out this artistic fantasy—whether for viewer or actor. I’ve recently found the perfect place to experience this connection.

Cloverdale Playhouse, housed in a 1930s church, is the location of something spectacular—something that has disappeared into the abyss. The Playhouse serves as a gathering place for a community of locals, working (and playing) together to create something magical. This big, happy family, disguised as teachers, shop owners, massage therapists, and restaurateurs, gathers with one goal in mind—to create a creative outlet for ordinary locals—just like themselves—to be something more. It is the place at the forefront for the redevelopment of our creative community.

As I sat with the actors of Cloverdale Playhouse, they didn’t even need to talk for me to experience the passion that was dripping from their cells. Whether they had been acting for 60 years or 6 months, the commonality shared by this group of people—who actually highly differ in age, profession, and every other regard—is something to be seen, and you’ll see this unspeakable bond in the magic that happens on stage.

The group of actors I had the pleasure of talking with—including Eleanor Davis, Jonathan Conner, Emily Lowder Wootten, and Sarah Thornton—were so passionate about expressing the importance of a community theater in Montgomery. Our city is bursting with creative beings that have a burning desire to act without necessarily making a life out of it. Cloverdale Playhouse gives these citizens the opportunity to act while still leading their already established lives. And the Playhouse truly is a community effort, with every single person being a volunteer—from the sound guy to the set designers. Everyone.

The Playhouse believes in using the resources available to them. They don’t go out searching the world for the perfect actor to play the part—they use people who have ties to Montgomery and a passion to do what they love. This simple mantra forces them to stick to the basics, to the true meaning of theater—telling a story that is both satisfying to an audience and gratifying to the actors. This also allows everyone involved to try new things without having the hierarchy usually seen in the theatre world lingering above their heads.

And don’t be disheartened that these actors aren’t “professionals” (by “professional” standards). Their unveiling passion trumps over a silly, little title. And not only do they have passion, but every single actor involved with the Playhouse is extremely talented (the proof is in their sold out shows). All are surprised at the level of goodness the actors possess. Hey, you know they’re talented when 13 people are playing 24 parts…

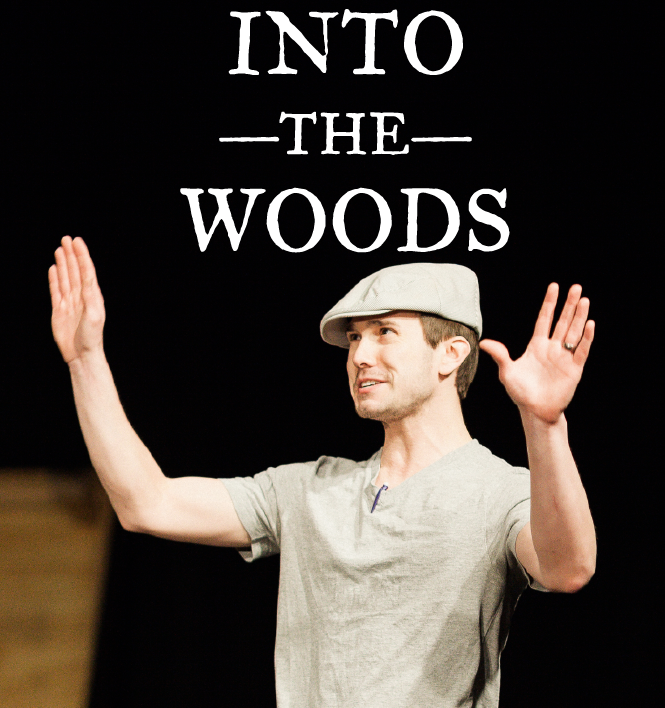

Jonathan Conner, who plays multiple parts in the upcoming production, Into the Woods, explained his reasons for getting into theatre—all of which are intangible. He believes that testing his own boundaries constantly keeps him on the edge of his own seat and getting into character forces him to understand his fellow man. Eleanor Davis, who has been acting for SIXTY YEARS, was thrown into the spotlight at an early age, as her parents made her perform at dinner parties held at their home. She swears if her father didn’t pass at a young age that he would have pushed his blonde-haired baby all the way to Broadway. She has been at the forefront for community theatre in Montgomery for years.

Emily Lowder Wootten, a UGA theater graduate and former actress on the Chicago theater circuit, quickly learned that she didn’t like being told no, and this outlet allows her to continue living her passion without encountering the harshness of the theater world. Sarah Thornton, who is the assistant director for Into the Woods, has been surrounded by theatre her entire life. She grew up in the hallways of the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, where her father acted as artist director. This forced her to fall in love with the beauty of a story. Currently, Sarah lives in New York City where she is involved with Bama Theatre Company—a place where alumni from ASF perform entire plays out of a single trunk.

The Playhouse is currently in their third season and their upcoming production of Into the Woods begins February 13th and runs through the 23rd. The musical, written by Stephen Sondheim, combines stories from the Brother Grimm into an epic fairy tale where worlds collide. It is the story of what happens after happily ever after. And although these fairy tales were written centuries ago, this particular musical merges them with real people and real problems, exposing daily issues we all face. It makes the characters human, as they must make real choices about real things, things that have consequences. The story is both hilarious and touching. The actors of the Playhouse even admit to crying randomly during rehearsals because their hearts were touched by the story.

Everyone should jump at the opportunities available to become involved with Cloverdale Playhouse. They are always looking for volunteers. And don’t be scared—they didn’t make me recite every Tony award winner from the beginning of time or list every play written by Shakespeare. The pretentiousness is left at the door, and these fine people will bring you into their family and make you feel right at home. As Randy said, everyone has a sense of being, a sense of being a part of something larger than just a play.

So come hang out with us. We’ll find something for you. And whatever you’ll be doing, you will be helping to provide our community with the fostering of artistic opportunities. And that, my friend, is something to be cherished.

For more information about classes, productions, and volunteer opportunities, visit

www.cloverdaleplayhouse.org and join the Cloverdale Playhouse group on Facebook.